FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

Gold 8 escudos Royal recovered from the 1715 Fleet shines in Sedwick’s November auction

Winter Park, Florida – October 7, 2020 – A Royal gold 8 escudos, a coin literally “fit for a king,” recovered from a sunken Spanish treasure fleet will be up for sale on Nov. 17 in Daniel Frank Sedwick, LLC’s Treasure Auction 28. It is graded by NGC as Mint State 66 and is the only example of its date slabbed by any third-party grading company. The auction firm estimates the coin at $300,000 and up.

“This coin is the pinnacle of Spanish colonial numismatics,” said Daniel Sedwick, president and founder of the company. “As a Royal 8 escudos, it is a coin so large, beautiful, and perfect as to be considered among the most desirable gold coins in the world – both then and now. It represents the finest in colonial minting abilities at the time. Plus, when you consider this specimen’s documented discovery on one of the most famous shipwreck sites ever, you realize just how truly special and rare this coin is. We’ve sold hundreds of gold cobs from the 1715 Fleet but this is the first time in 14 years of auctions that we’re offering a 8 escudos Royal.”

Ben Costello, president of the 1715 Fleet Society, called the coin a superb specimen with a securely documented provenance to the Corrigan’s wrecksite of the 1715 Fleet.

“Fleet collectors are delighted by the first time offering of this gorgeous and very rare 1713 8 escudos Royal,” said Costello. “Only two examples are known. This piece is surely among the best, if not the best, of the entire 1711 to 1713 series of cross-with-crosslets Royals.”

The specially struck presentation piece was minted in 1713 at the Mexico City Mint and bears the oXM mintmark to the left of the shield. Below the mintmark, the initial J stands for assayer José de León, the mint official responsible for the entire coinage production. The Royal shield and crown at the center stand for King Philip V’s authority over Spain and her colonies. To the right of the shield is a vertical VIII representing the 8 escudos denomination. The legend reads PHILIPPVS V DEI G 1713 with florets in the spaces between words. The DEI G stands for Dei Gratia, “by the grace of God.”

On the reverse, a framed cross is in the center with stylized fleurs-de-lis in the quadrants. The legend there is HISPANIARVM ET INDIARVM REX (“King of Spain and the Indies”) with florets in the spaces between the words and a smaller cross at the top.

What sets a Royal, also known by the Spanish term galano, apart from the regular cob issues is its detailed, even striking on a specially prepared, round planchet of uniform thickness and weight. The regular cob coinage was quickly produced in quantity by hammering irregular planchets. Often, whole portions of the design were weakly struck or missing entirely. This is not the case with Royals.

From start to finish, the production of a Royal was a careful, thoughtful process. The dies were specially prepared with design elements accurately punched in to maximize detail. The gold planchet used was of full weight and a uniform, round shape to fit all of the design. Finally, a mint worker would strike the planchet with the hammer die using uniform, strong pressure – a very difficult task. Afterwards, a gold Royal would be handled differently and not transported in large sacks or casks with regular coins. By intention, very few cob 8 escudo Royals were minted due to the time and resources it took to make them.

After being struck at the mint, this Royal 8 escudos departed the New World aboard a Spanish galleon in the 1715 Plate Fleet. Its destination was mainland Spain, where it would have been given or awarded to an important Spanish official or member of the Royal family. The King of Spain himself was also possibly an intended recipient of gold Royal coins.

In addition to several other Royals (the 1715 Fleet is the primary source for gold 8 escudos Royals), the ships carried a wealth of treasure: silver and gold coins from the colonial mints, fine jewelry and religious objects, precious gemstones, spices, and Kangxi china from the Manila trade route. Even large quantities of contraband were smuggled onto the ships, bypassing the tax that was to be levied to the King.

Much of the official treasure onboard was intended to refill Spain’s coffers. The kingdom’s finances were in disarray following the misrule of King Charles II and the subsequent War of Spanish Succession. Spain was reliant on the annual voyages from the New World to bring wealth to the mainland. The war and its political instability had delayed the fleets and large quantities of treasure had piled up in Mexico and Colombia. The fleet, carrying enormous amounts of treasure from an entire continent, needed to arrive in Spain soon.

The fleet itself was a combination of two fleets, the combined Tierra Firma Fleet coming from Cartagena loaded with Peruvian and Colombian treasures, and the New Spain Fleet coming from Mexico with coins, gemstones, and china. The combined flotilla was comprised of eleven Spanish vessels with a single French vessel, the Griffon, tagging along. On July 24, 1715, they departed Havana, Cuba on a north-northeasterly course to sail along the east coast of Florida before crossing the Atlantic and onwards to Spain.

Having initially left under fine sailing conditions, the fleet soon encountered violent weather and, by July 30th, entered the path of a hurricane. In the early hours of July 31st, just off Florida’s coast between what is now Cape Canaveral and Fort Pierce, the eleven Spanish ships were cast upon shoals by the waves and destroyed. Close to 1,500 sailors and officers were killed. The treasure cargo was scattered across the ocean floor as the ships broke apart. The survivors who made it ashore were spread across the coast for miles. Only the French vessel Griffon made it through the storm and continued on to France, unaware of the Fleet’s annihilation.

The survivors, led by Admiral Don Francisco Salmón, set up camp and sent a small party to Cuba to deliver news of the tragedy and launch a rescue mission. Spanish authorities in Cuba dispatched several ships to supply the survivors and begin salvaging the sunken treasure. For months, the Spaniards worked the waters off the coast, recovering millions of coins and a good amount of artifacts. Pirates who learned of the Fleet’s destruction harassed the Spanish salvors and made off with even more treasure.

By 1718, the Spanish had considered their salvage operation a success and departed the area. Even then, significant amounts of treasure remained just off Florida’s shore, buried in the sand and trapped beneath debris. For almost 250 years, the coins and artifacts would remain lost – among them this 1713 Royal 8 escudos.

By the 1960s, advances in diving technology and metal detecting allowed determined seekers the chance to find Spanish colonial coins from the Fleet along the beaches between Melbourne and Stuart (an area now called the Treasure Coast). Retired building contractor Kip Wagner and the Real Eight Co. organized salvage operations on what eventually became eight known wreck sites of the 1715 Fleet (at least three of the ships have yet to be located). In conjunction with the State of Florida’s lease system, the salvors were able to recover large quantities of shipwreck silver and gold coins in addition to artifacts and jewelry.

This 1713 Royal 8 escudos now being offered was recovered on Aug. 16, 1998 by diver Clyde Kuntz. Kuntz, operating from the salvage vessel Bookmaker captained by Greg Bounds, was diving on the Corrigan’s wreck site just north of Vero Beach. The site, then leased by the Mel Fisher company, is named for Hugh Corrigan who owned a house on the beach there.

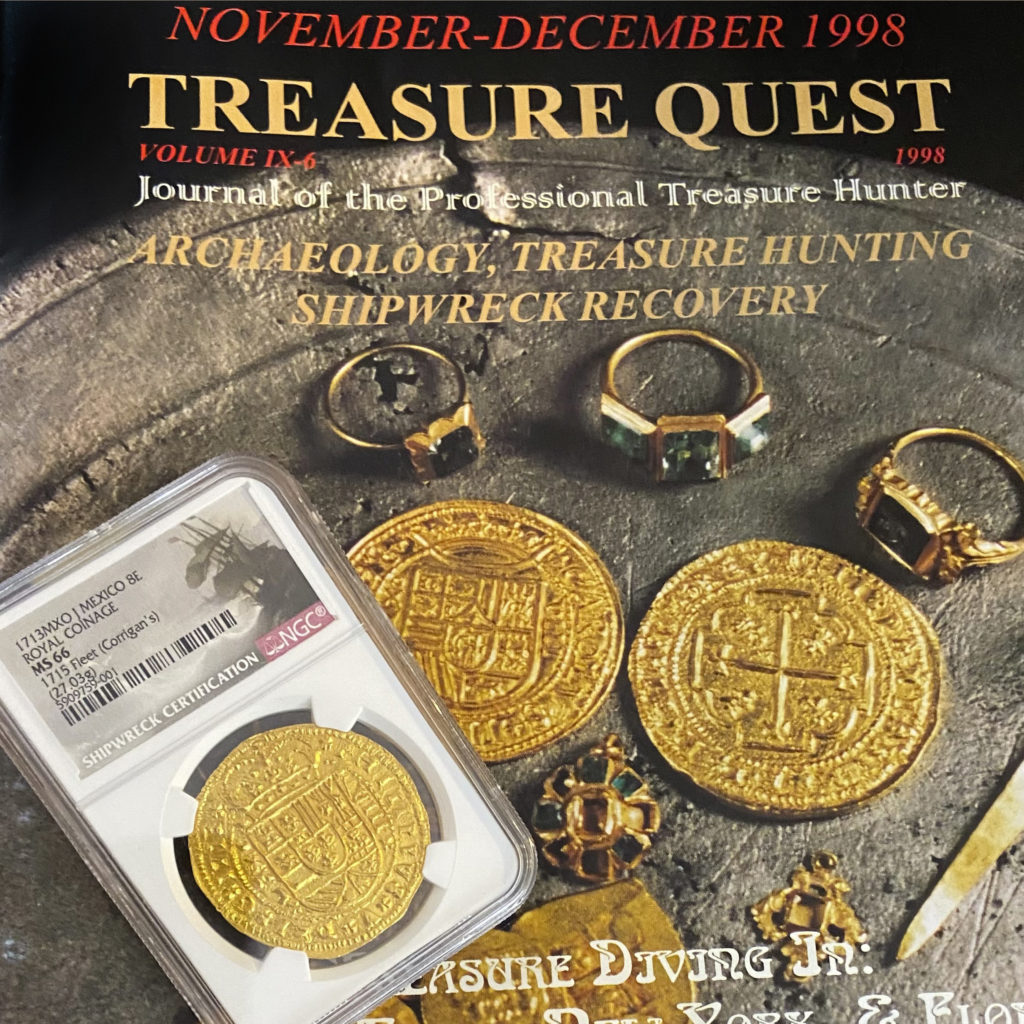

On that day, Kuntz was searching several holes in the ocean floor. Around the third hole, he pulled a gold cob 8 escudos Royal dated 1698 from a crack in the hard pan (a coin that, to this day, is unique). He stored it in his facemask to ensure he didn’t lose the valuable find. He returned to the salvage vessel to much elation among the crew for the impressive find. Then, upon returning to the water, he searched another hole and located the gold cob 8 escudos Royal now being offered. This time, he kept the coin in his diving glove so it could not be lost again. The discovery of two cob 8 escudos Royals in one day attracted much attention and the covers of several salvage publications featured both coins.

After the finding, this 1713 8 escudos Royal was documented and tagged in accordance with the State of Florida’s treasure hunting laws. The state, using a point-based system, receives 20 percent of each year’s finds and first choice among the items recovered. Upon the division, this coin was returned to the salvors for private sale. It spent many years off the market, residing in the numismatic cabinet of numismatist Isaac Rudman.

Throughout its 307 year journey, from the mint to the fleet to the ocean floor, it has remained as bright and original as the day it was made. Its surfaces shine with flashy yellow luster as its gold was unaffected by the corrosive effects of saltwater. The design is crisply rendered by a strong, even strike that is well centered on the large, flawless planchet. This coin is the closest to perfection that Spanish colonial cob coinage could ever achieve.

The coin will be sold on Nov. 17 in Sedwick’s auction as lot 21. Online registration is now available at the auction site, auction.sedwickcoins.com. Auction lots will be available for online viewing starting Oct. 19.

Press Contact:

Connor Falk

Daniel Frank Sedwick, LLC

P.O. Box 1964

Winter Park, FL 32790

407-975-3325

connor@sedwickcoins.com

Photos:

Obverse of the Mexico City, Mexico 1713J cob 8 escudos Royal

Reverse of the Mexico City, Mexico 1713J cob 8 escudos Royal

Front view of the 1713J cob 8 escudos Royal in its NGC Mint State 66 slab

The 1713J cob 8 escudos Royal on the November-December 1998 issue of Treasure Quest magazine where its discovery was reported

This “Day After” painting by Ralph Curnow illustrates what the fleet’s ships would have looked like after their destruction in the hurricane